The winter of 1933 was one of the coldest Iowa had known in years. The Great Depression had stripped towns bare of hope, leaving only frostbitten mornings, silent breadlines, and the long shadows of freight trains cutting across the snow. It was on one of those trains—steel beasts that carried the restless, the desperate, and the unwanted—that a teenage boy named Michael Cleary began his journey.

Michael had started out from California, too young to be hardened yet too old to still believe that the world would hand him fairness. He was lean from hunger, his clothes frayed, the wind slicing through his coat as though it were gauze. To him, the boxcars were both coffin and cradle—carrying him toward unknown futures, yet always one slip away from death.

On one bitter evening, outside the rail yards of Des Moines, Michael clung to the side of a freight train. The bulls—the railroad police—were merciless. If they caught him, he’d be beaten bloody or worse, left to freeze. He’d learned the art of leaping from moving trains when danger came close, the bruises of practice still mapped across his ribs. That night, he saw another hobo, older, exhausted, lose his grip on the ladder. The man’s legs disappeared under the grinding steel wheels in a sickening instant. Blood steamed against the snow, and Michael, his own heart splitting, dragged the man from the tracks. Against every cold wind, he hauled him—an almost lifeless stranger—toward the faint red cross glowing above a hospital building in the distance.

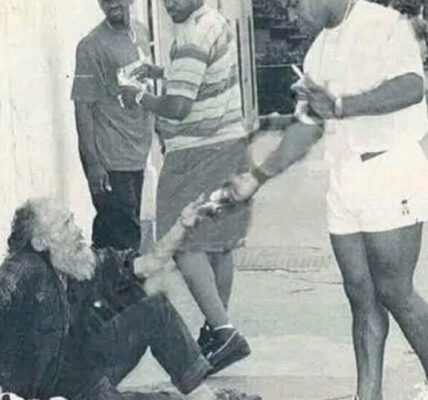

The man lived, though his legs were gone. Michael never saw him again, but the memory seared into him: survival, he realized, was not only about his own hunger or safety. It was about refusing to let another soul vanish unseen into the cold machinery of history.

In the days that followed, Michael lived the way so many Depression-era drifters did—by taking what scraps of work he could. He stacked wood for pennies. He unloaded coal for endless hours, the black dust embedding itself into his fingernails. He even cared for an elderly man for a single dollar a day, carrying firewood into his home and listening to stories of a world before the crash. Those jobs did not make him rich—they barely kept him alive—but they taught him something rarer than money: the worth of self-reliance, humility, and mercy.

The Great Depression hollowed out America, but in those hollows, strange pockets of grace appeared. Sometimes it was a crust of bread shared among starving men beneath a bridge. Sometimes it was a stranger who offered you a blanket without asking your name. For Michael, it was the small mercies that mattered most—the kindness that could never erase the hardship, but could transform the meaning of survival.

Years later, when his hair had silvered and his children sat at his feet, Michael Cleary told them of those winters on the tracks. He described the men with haunted eyes huddled around fires, the brutality of the bulls, the hunger that never fully went away. And he told them of the night he carried a broken man from beneath the train’s steel teeth to the door of mercy.

“Those bloodied tracks and small mercies,” he whispered to his grandchildren, “showed me that survival isn’t just enduring—it’s lifting others when the world weighs you down.”

In that moment, his story was no longer just his. It became a parable for generations, a reminder that even in the bleakest winters of history—whether in the Great Depression, the Holocaust, or the darkest wars—human dignity is measured not only by what we endure, but by how we refuse to let others fall.

Michael’s legacy was not the scars of hardship, but the strength to carry another man when the world tried to crush them both. That is the story of America’s hobo jungles, of the wandering souls who kept kindness alive amid hunger, and of the boy who learned that the truest wealth is compassion.