The Battle of Yorktown, fought from September 28 to October 19, 1781, was more than the final chapter of a long war; it was the moment when the fate of a fragile dream was written in blood, sacrifice, and unshakable resolve. To reduce Yorktown to numbers—7,000 British soldiers surrendered, two weeks of siege, one treaty of peace—is to miss the heart of the story. Yorktown was the culmination of human endurance, where ordinary farmers, blacksmiths, and merchants, hardened by years of suffering, rose to define the destiny of a nation.

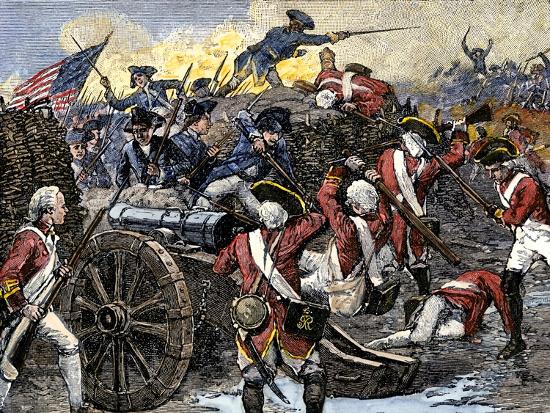

In the chaos of smoke and cannon fire, one figure captures the soul of the moment: a Continental soldier, his blue coat tattered, his tricorn hat askew, standing defiantly atop a captured redoubt. His musket, raised high toward the gray sky, is not just a weapon—it is a declaration. Dirt streaks his cheeks, his hands tremble from exhaustion, yet his eyes shine with a quiet fire. Behind him, the flags of America and France ripple together in the breeze, symbols of a partnership born out of desperation but destined to deliver liberty.

This man was not a mythic hero carved from marble. He was a son who left a mother’s embrace, a husband who promised his wife he would return, a farmer whose calloused hands once tilled the soil now wrapped around cold steel. His face is every face of the Revolution—scarred, weary, yet unbroken.

For weeks, General George Washington and the Marquis de Rochambeau led their combined armies in a relentless siege of Yorktown. Every night, men dug trenches under cover of darkness, their shovels striking the earth with a rhythm of survival. They marched barefoot on splintered boards laid across mud, carried supplies on backs already bent by years of war, and bore the thunder of British artillery that shattered the silence of dawn.

The French fleet under Admiral de Grasse had sealed the Chesapeake Bay, cutting off escape and supply for General Cornwallis. With every day that passed, the circle around the British tightened. Yet victory was never certain. Hunger gnawed at the bellies of the soldiers. Fever spread through the camps. Letters from home reminded them of families left in despair.

Still, they pressed on. Hope was the only ration that never ran out.

On October 19, 1781, silence replaced the roar of cannons. Cornwallis, unable to escape, sent his officers forward to surrender. The red-coated soldiers, once symbols of imperial might, marched solemnly to lay down their arms. Their drums beat a hollow sound, not of triumph but of resignation. Some wept quietly, others stared blankly at the soil of a land they could never claim.

For the Continental soldiers, the moment was surreal. Years of hardship—marches through snow at Valley Forge, hunger that drove men to eat leather from their boots, endless battles where comrades fell beside them—had led to this. Freedom was no longer a dream whispered around campfires; it was a reality taking its first breath.

One eyewitness recalled that as the British stacked their muskets, American soldiers did not cheer wildly. Instead, they stood in solemn silence, as if aware that liberty had been purchased with too high a price to celebrate with noise. The graves of the fallen stretched behind them; their silence was an act of remembrance.

Yorktown was a triumph, but it was also a graveyard of dreams. Thousands had died over the course of the Revolution, and countless families bore scars that no peace treaty could mend. Wives became widows, children grew up fatherless, and entire towns had been reduced to ashes.

Slaves who had fled plantations to fight for the promise of freedom often found themselves returned to bondage. Native nations who had aligned with either side faced broken promises and encroachment on their lands. Independence for some meant dispossession for others.

Even for the victors, victory was not free. Many soldiers would limp home to farms they could no longer manage, debts they could never repay, and wounds—both physical and invisible—that never fully healed.

Yet in that bittersweet silence at Yorktown, something extraordinary was born. The Treaty of Paris in 1783 would officially recognize the United States as an independent nation. What had begun as scattered resistance in small towns like Lexington and Concord ended in the recognition of a sovereign people determined to govern themselves.

Yorktown became more than just a battlefield. It became a symbol of international cooperation, of strategic brilliance, and of the sheer resilience of the human spirit. Washington, Rochambeau, Lafayette, and de Grasse etched their names into history, but so too did the nameless farmer-soldier who raised his musket in triumph, never to be remembered except as a whisper in the story of freedom.

Today, when one walks the fields of Yorktown, the silence feels almost sacred. The earth still bears the faint lines of trenches, the cannons stand as cold sentinels, and the wind seems to carry echoes of that October day. Visitors see more than relics—they see the cost of liberty etched into the soil.

Yorktown reminds us that freedom is never free. It was paid for with hunger, with grief, with blood, and with the dreams of those who would never live to see the dawn of independence. Yet it also reminds us of resilience—the power of ordinary people to stand against empire, to fight against despair, and to win a future they believed in.

The Battle of Yorktown was not simply a military victory; it was a turning point in human history. It marked the moment when thirteen colonies, fragile and divided, emerged as a nation united by sacrifice. The soldier raising his musket in triumph is not just a figure of the past—he is a reminder to every generation that liberty must be earned, defended, and cherished.

The smoke has long since cleared, but the spirit of Yorktown endures. It is the spirit of men and women who gave everything for a promise—that a new nation, conceived in liberty, might stand the test of time.