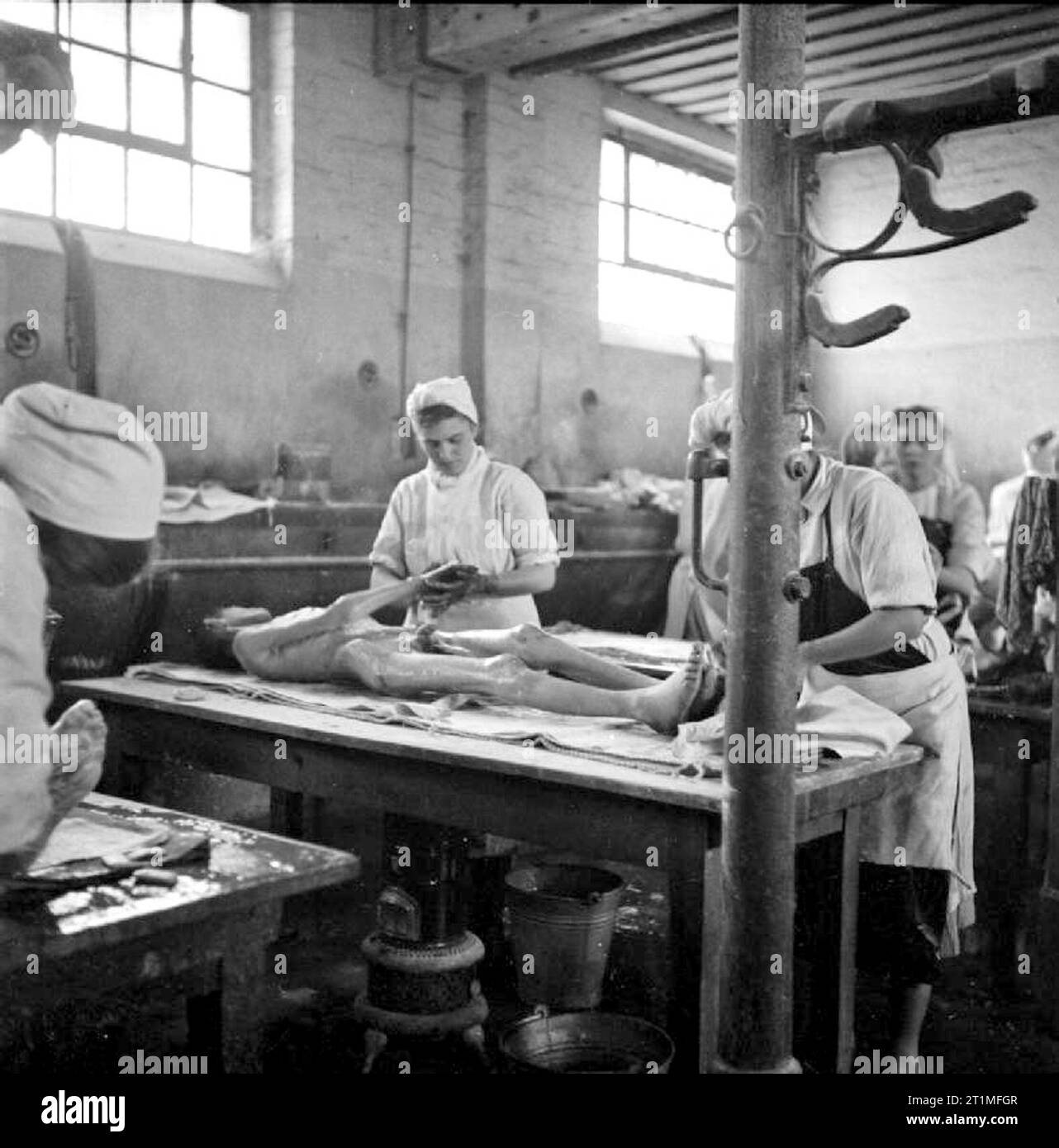

When the gates of Bergen-Belsen swung open in April 1945, the British soldiers who entered expected to find prisoners. What they found instead was a graveyard of the living. The air was heavy with rot and silence, broken only by the faint groans of those who clung to life. Emaciated figures lay scattered in the mud, some too weak to lift their heads, others already stilled by death. It was not a camp any longer; it was a wound on human

Among the chaos, one woman emerged as a fragile beacon of mercy. She wore the uniform of a nurse, though no training could have prepared her for the nightmare before her. In her hands, she carried only a single tin of water. It was not much—barely enough to soothe even one parched throat—but she carried it as though it were holy.

She moved from body to body, bending low, whispering words in broken German, English, and sometimes only in the universal language of compassion: “Hold on. You are free now.”

Most were too weak to drink, their mouths cracked, their tongues swollen. She wet their lips instead, letting a single drop touch them like a sacrament. For some, it was the first kindness they had received in years. For others, it was the last.

Bergen-Belsen was not built to kill with gas chambers, but it killed nonetheless—through hunger, disease, neglect, and cruelty. When the liberators arrived, they found nearly sixty thousand prisoners in various stages of starvation and sickness, and another thirteen thousand corpses unburied.

The nurse who carried water—her name long forgotten in the tides of history—did not ask who they were or what languages they spoke. She saw only suffering, stripped of all distinctions. Jews, Romani, political prisoners, children—all were equal in their thirst.

One survivor would later recall: “We could not lift our heads, but I remember the hand on my lips, damp with water. It was not enough to live, but enough to feel human for a moment.”

For the British medics and nurses, Bergen-Belsen was not a triumph but a torment. They had come as liberators, yet found themselves powerless against the scale of death. Food, if given too quickly, killed the starving. Water, if swallowed too fast, drowned the frail. Medicine arrived too late for tens of thousands.

The nurse’s small act—running from tent to tent with her single tin—was both an act of mercy and an acknowledgment of helplessness. She could not save them all. She could not even save most. But she refused to do nothing.

Each time she bent down, she risked despair. Each pair of eyes she met forced her to witness suffering so profound that it carved itself into memory. Yet she carried on. That was her battle.

The camp survivors who were strong enough to speak remembered her not for curing them, but for acknowledging them. In Bergen-Belsen, prisoners had been reduced to numbers, stripped of names, of dignity, of the smallest gestures of kindness. A sip of water, a whispered promise of freedom, was a defiance against that annihilation.

One man later told of how he tried to form words when she touched his lips with water. His voice was gone, but he remembered her smile, soft and sorrowful. “It was the first time in years,” he said, “that someone looked at me as if I was alive.”

History rarely records the faces of those who gave comfort more than those who gave pain. We know the names of commanders, of tyrants, of executioners. But the nurse at Bergen-Belsen remains nameless, a shadow among the living dead.

And yet, in her anonymity, she becomes universal. She is every nurse who chose compassion over despair, every medic who bent over a dying stranger and refused to walk away. She is the embodiment of the belief that even in the darkest pit, humanity can still flicker.

When she returned from the camp, she carried more than her tin cup. She carried memories that would haunt her for the rest of her life—the stench of death, the skeletal faces, the whispered gratitude of the dying. Many nurses who served at the liberation of concentration camps spoke later of nightmares, of guilt, of never being able to reconcile the little they could do with the enormity of suffering they witnessed.

In today’s world, where wars still rage and refugees still wander without homes, the story of the nurse who carried water forces us to confront a truth: survival is not only about grand victories but about the smallest mercies.

Her tin of water did not change the outcome for most at Bergen-Belsen. Thousands died even after liberation. But for those whose lips she touched, whose eyes met hers in that final moment, her act mattered. In a place built to strip human beings of dignity, she gave it back—drop by drop.

We often think of heroism in terms of soldiers charging into battle, of generals commanding armies, of leaders signing treaties. But there is another kind of heroism—the quiet, uncelebrated courage of those who simply choose kindness in the face of despair.

The nurse who carried water is a hero not because she ended the Holocaust, but because she refused to let suffering go unanswered. She believed that even the dying deserved dignity, that even the defeated deserved compassion.

History books record that Bergen-Belsen was liberated on April 15, 1945. They record numbers, statistics, dates. But somewhere among those numbers lived a nurse with a tin of water, who believed that humanity was worth fighting for even when humanity seemed already lost.

Perhaps that is why her story lingers—because in the end, it is not the scale of what she accomplished that matters, but the depth of what she refused to surrender: mercy.

In a world built on cruelty, her act was a rebellion. In a place of death, she offered life. In the silence of despair, she whispered hope.

And though most who felt her touch did not survive, their final memory was not of barbed wire or hunger, but of a stranger’s hand carrying water, and the words: “Hold on. You are free.”